The Pyx is an obscure movie adapted from an obscure book written in 1959 by an obscure Canadian professor named John Buell. Buell's short (our Crest paperback edition is 128 pages) hardboiled detective story-cum-satanic cult expose is really more of a novella. The task of committing it to celluloid was taken on by director Harvey Hart, a Canadian better known for his work in TV at that point. It's worth noting that Ranting Russell founder Russell Bladh has always had a soft spot in his heart for Harvey Hart, as the Toronto-born director/producer helmed both the 1st-season Star Trek episode Mudd's Women, and the 1st-season Wild Wild West episode The Night of the Dancing Death. With respect to the latter, Mr. Bladh - before he had a breakdown and was committed - always said it contained one of the greatest lines in television history: "Death is your destination. I hope you had a good look." He actually used to say this randomly to staff, walking around the office.

Struck by such a morbidly catchy line, staff went back and watched the episode, discovering guest star Peter Mark Richman actually says "That is your destination" (he's motioning towards a big hole in the floor, through which he intends to throw Robert Conrad). We decided against telling Russell he misunderstood it. Dude had enough on his plate already.

Buell structured his book with The Present and The Past chapters, beginning in The Present, and alternating a total of six times between the story of junky prostitute Elizabeth Lucy getting set up with the mysterious Mr. Keerson, and Lieutenant Henderson's investigation of Lucy's apparent suicide, falling from the top of an 11-story apartment building. Screenwriter Robert Schlitt, who also spent most of his career in television, ran with this structure, upping the ante to give the story more oomph in a visual medium: instead of just six jumps in time, the movie jumps 26 times, and does so fluidly and with a decent amount of tension, thanks to the editing skills of a then-young Ron Wisman.

The Pyx is a great example of filmmakers adapting a book for the silver screen and having zero interest in casting actors even remotely resembling their literary counterparts. This staff positively adores Humphrey Bogart, but remember The Maltese Falcon's killer opening paragraph, where Hammett writes "Samuel Spade's jaw was long and bony... his pale brown hair grew down - from high flat temples - in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blond Satan," and then they cast Bogie as Sam Spade in the movie, who looks nothing whatsoever like a blond Satan?

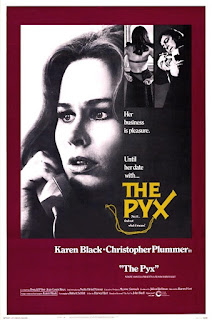

Here we have the book describing Lieutenant Henderson as "in his fifties, balding and greying, with a tall, heavy, now paunchy body." In the movie Henderson is played by Christopher Plummer, who was 44 at the time, sporting a full head of dark hair, trim and handsome. We grudgingly accept the casting department's decision, as we all love Christopher Plummer. But really...?

Our heroin-addicted heroine is played by Karen Black, just three years after her outstanding turn in Five Easy Pieces, and just a couple of years ahead of her finding Scientology. (Still, Trilogy of Terror wouldn't have been the same without her. - Ed.) Black is outstanding here, lifting up an otherwise prosaic movie with her portrayal of the doomed Elizabeth, who knows something isn't quite copasetic with the john her boss Meg Latimer is setting her up with, but senses it is a very bad situation indeed. Things get weirder when Meg forces her to meet in private with the mysterious Mr. Keerson, played with suitable menace by Jean-Louis Roux, who orders her to disrobe and tell him about her life, all while staring right into her eyes, never ogling her body.

This would already be a wonderfully unpleasant and awkward scene, but director Hart does something interesting here, overlaying the second movement of Bach's Violin Concerto in A Minor (BWV 1041) - and LOUD - over the whole scene in real time. The juxtaposition of one of the most sublimely beautiful pieces of music in history with the evil Keerson psychologically probing naked Elizabeth isn't as unnerving as it should be, but we still give Hart props for trying something wholly unexpected. If you want to see what happens when the perfect piece of classical music is embedded in a movie, check out the POV scene in The Black Cat where Karloff leads Lugosi through the old chart room for long-range guns in the ruins of Fort Marmorus, after showing Lugosi how he's preserved his (Lugosi's) dead wife in an upright glass container. Against the haunting strains of the 2nd movement of Beethoven's 7th Symphony, Karloff delivers an astonishing soliloquy, qualifying for Best Movie Scene No One's Aware Of. Go watch the 1934 Black Cat this instant if you've never seen it.

The upshot to all of this - Keerson hired Elizabeth to be sacrificed in a satanic Black Mass in his penthouse that ends with him tossing her off the top of a high-end apartment building - leads to a final scene that shows you how much potential this little movie had, but just didn't quite deliver on. Lieutenant Henderson tracks Keerson to his penthouse, where the mysterious businessman tells the detective his name isn't Keerson at all. "You know my name. You know it, Henderson. You know it better than anyone. When your wife died in that accident... you were happy. You felt liberated. My name touched you then. You went to confession but it didn't help. You couldn't forget. You didn't want to. You too felt the hypocrisy of the church."

Robert Schlitt's screenplay, serviceable until now, suddenly takes flight here. We discover a heretofore unreferenced catastrophe in Henderson's past (earlier in the film we see Henderson waking up at his girlfriend's apartment, desperate to leave, but no mention of a wife, dead or otherwise), explained with malignant glee by a man who is, apparently, possessed by Satan himself. But Keerson is just warming up: "You keep a little corner of morality inside that stinking soul of yours. A minor delusion to convince yourself that you still know good from evil. But you don't know it, Henderson. You don't know it 'til you touch it. 'Til you open yourself up to the power. When it manifests itself, then you know it. And it's there. It is. It exists. I've seen it. I've become it."

So we find out in the final four minutes of a 111-minute movie that the male lead has a dark secret, and that the villain has a penchant for delightfully evil monologs. We could have used a little more of both during The Pyx's runtime. There was potential here, but the source material was too hesitant to begin with, never doing a true deep-dive into moral depravity and the dark side of the human soul (in a passage from the book that fails spectacularly to convey the vibe of big city crime and despair, Henderson laments the trouble young women like Elizabeth get into, thinking "Mrs. Latimer would want the body, but alive, alive to peddle it, to feed it heroin, to dress it up, to make it entertain lechers who had nothing but money and erotic energy"), and in the final analysis we have to agree with writer John Kenneth Muir: The Pyx just isn't artful enough to make any forceful or memorable point about good and evil, sacrifice and virtue. It doesn't help that parts of the movie (if not all of it) were shot MOS with voices looped in post, lending the film a cheapness it never quite escapes from.

Keerson's spicy soliloquy, incidentally, doesn't appear in the book, and neither does the revelation that Henderson felt relieved when his wife died. In the book Satan appears to be speaking through Keerson and Henderson has to cold-cock him, after which Keerson comes to, yammering semi-coherently ("I can't control it anymore... after she... died it came over me fully, at last, with... I thought I had the power to... it felt as if I was ruling. But it's beyond me now... I can't command... the chaos") before Henderson plugs him.

...And if you're too dull to figure out what went on between Henderson and Keerson in that penultimate scene, "The Secret of The Pyx: A Postscript," by Daniel P. Mannix, is happy to beat you over the head: "The novel you have just read may have left you a bit mystified as to the true character of Keerson and the nature of the rites he intended to perform over the nude body of Elizabeth Lucy. Keerson had become a victim of demoniacal possession and was attempting as a Satanist to perform the terrible ritual of the Black Mass."

Geez, thanks, Mr. Mannix. Damned if I coulda figured that out on my own.

Mannix, incidentally, is the man who wrote Those About to Die in 1958, that Ridley Scott made into Gladiator with Russell Crowe. The movie steers clear of Mannix's asinine postscript and ends depressingly with Henderson standing over Keerson's body.

A pyx, for the Catholic among you, is a locket-like contraption that holds a host.